Stefan Moses, von Perckhammer and more

Interview with Dr. Kathrin Schönegg, Head of the Photography Collection at the Münchner Stadtmuseum

_______________________________________________________________

Ms. Schönegg, your visit to the Ullstein photographic collection for the informative book publication on Heinz von Perckhammer (1895-1965) was dedicated to the extensive holdings at ullstein bild, approx. 750 images. His photographs date back to the Weimar Republic and National Socialism, and he was obviously one of the profiteers of his time. He profited from the groundbreaking stylistic developments and possibilities of the photographic avant-garde of the 1920s, and he also profited from the order situation under a National Socialist regime that used the knowledge and skills he had previously acquired for its propagandistic purposes. How exactly did this kind of exemplary border crossing come about?

My work on the subject dates back several years. As a Thomas Friedrich scholarship holder in 2017, I spent a year researching the life and work of the photographer based on the Perckhammer collection in the Berlinische Galerie. The focus was on his active years as a photojournalist in Berlin from 1927 to 1943. In the sense of empirical basic research, the study aimed to make Perckhammer's work and his working conditions accessible: to compile a corpus of images, reconstruct the contexts of photographs, chronologize and date them on the one hand and research publishers, picture agencies and distribution channels on the other.

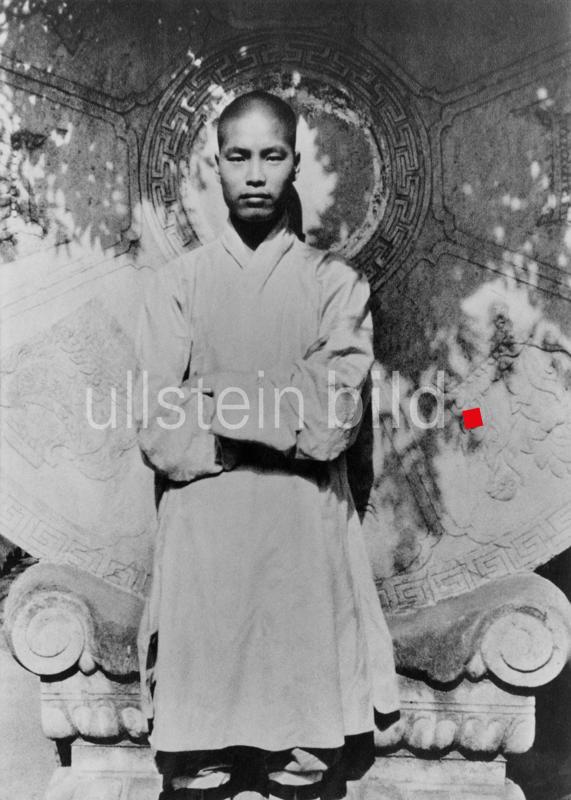

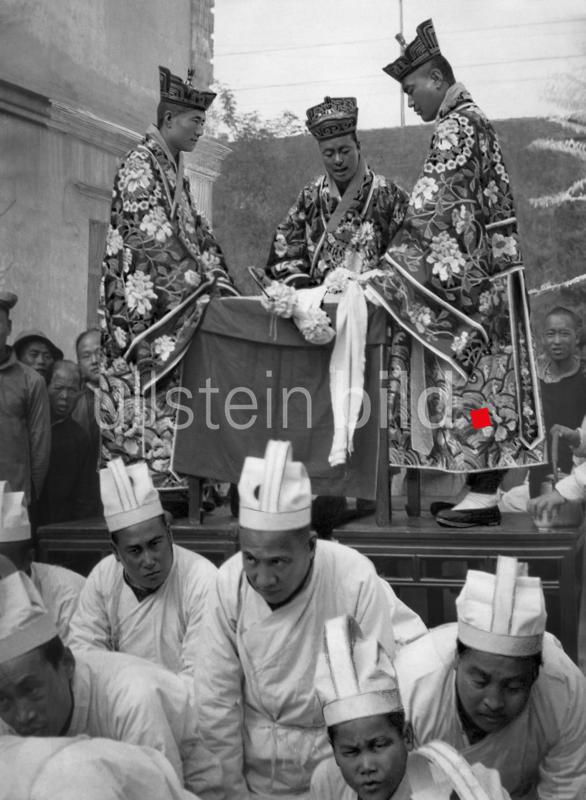

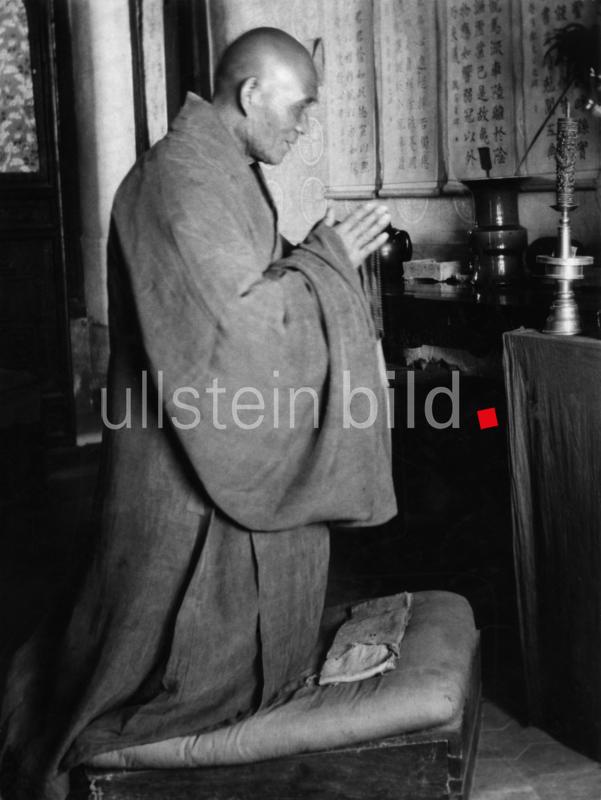

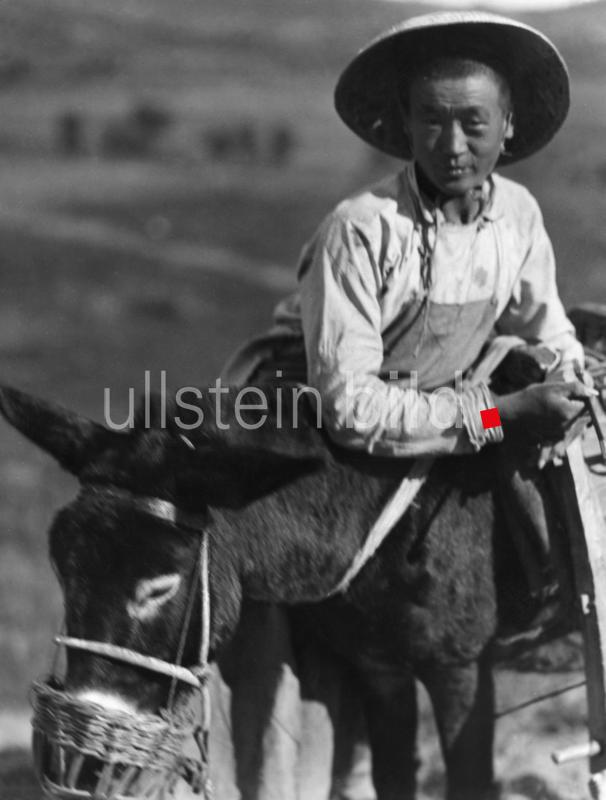

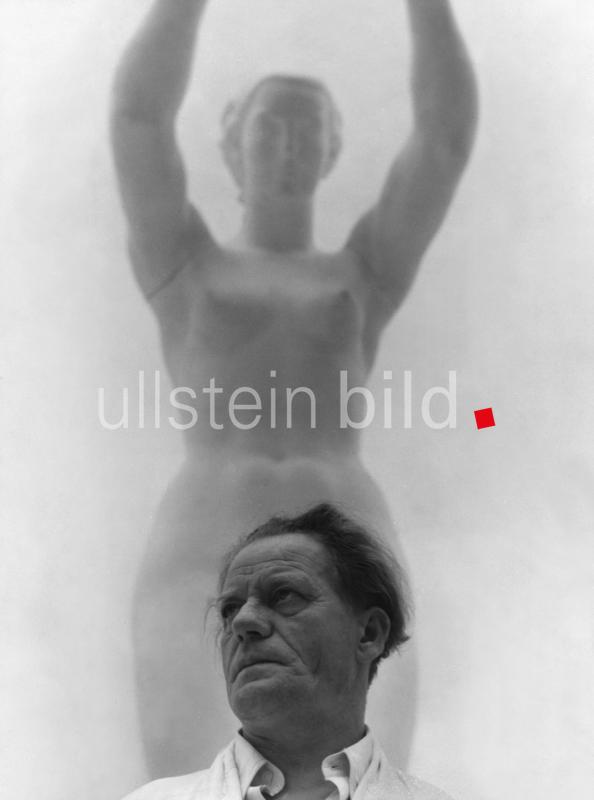

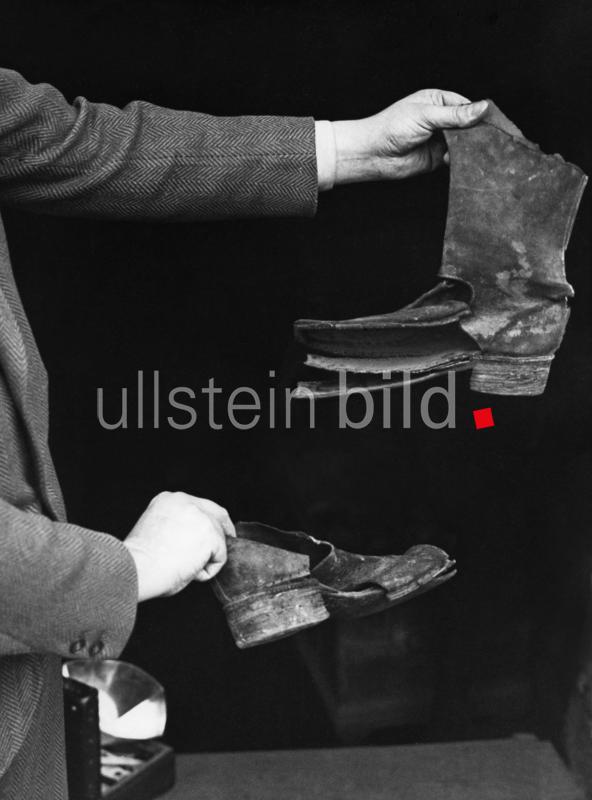

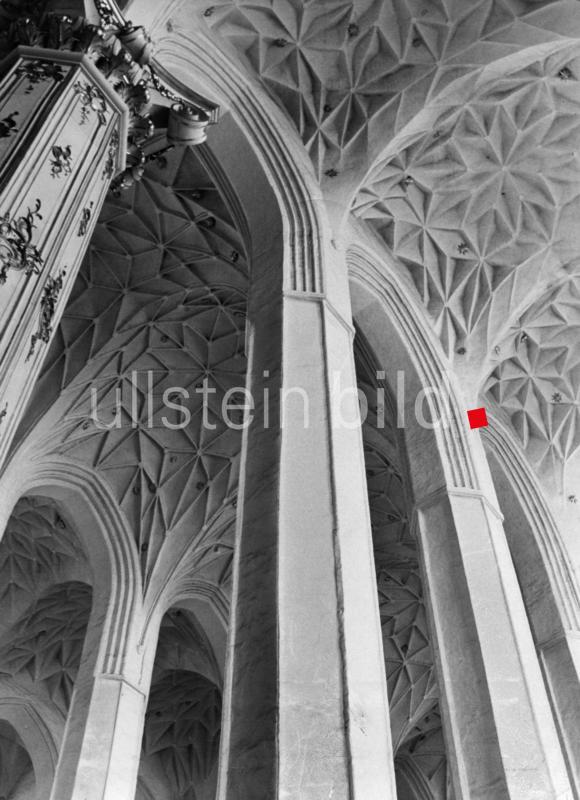

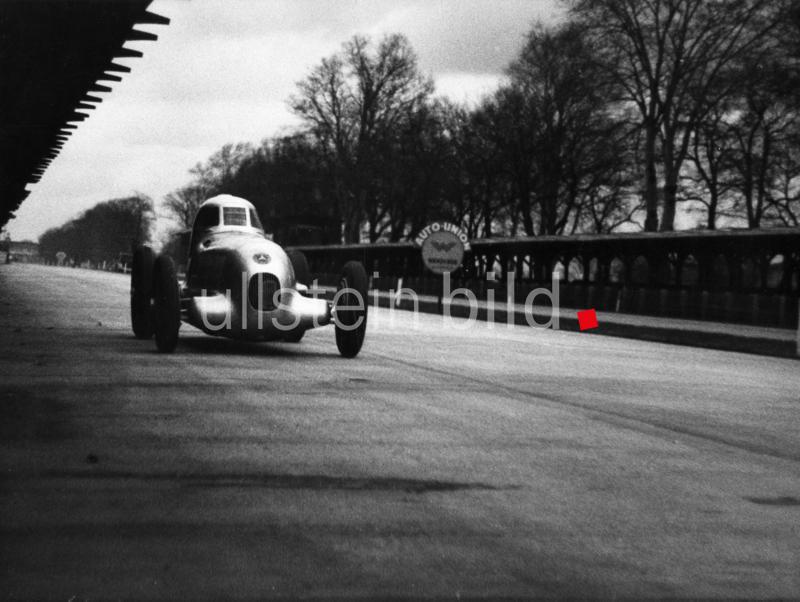

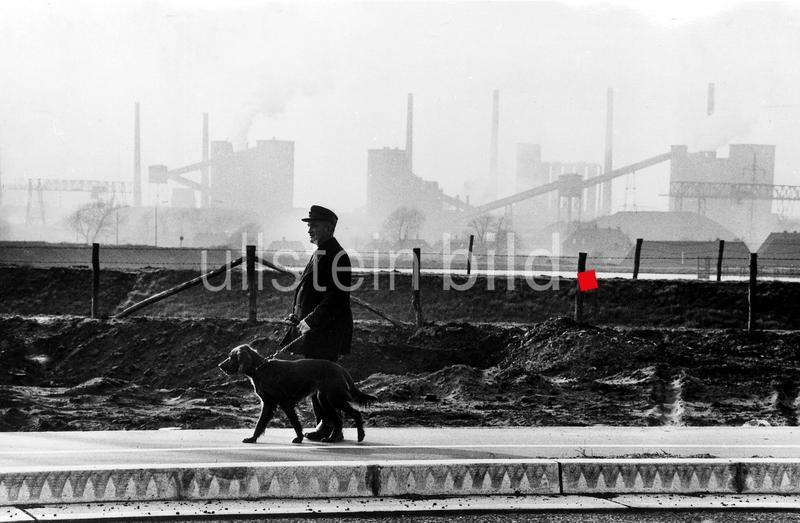

In the 1920s, he established himself through nudes and travel pictures, which he took during private trips. He documented the country and its people, depicted architectural and scenic features and portrayed professions and types in their respective environments. The modern city then broadened the range of subjects: department stores, fashion and social life in Berlin are now represented, as are the mountains, churches and skiers of his Tyrolean homeland, which he visited regularly. His illustration photography, which consisted of portraits, nudes and various genre shots, was published in photographic journals, illustrated magazines and the weekly press. (Sub)current photo reports and coherent reportage series, for example of the car races on the Berlin AVUS racetrack or the Zeppelin's world tour, are mainly published by August Scherl Verlag. After 1933, it is easy to see how the stable of image suppliers shrank drastically over the years of Nazi rule. Von Perckhammer is represented almost weekly until 1941 with alternating modern and nationalistic genre pictures, which were explicitly used here and elsewhere in the service of propaganda.

Von Perckhammer benefited from the fact that his themes seemed to fit seamlessly into the changing socio-political environment: Car and motor sports, social life, fashion. Some old and many new images fitted into the canon of National Socialist values and were used to illustrate ideologies such as the homeland or racial purity. In terms of form and content, he oscillated between country and city, tradition and modernity. He repeatedly used the same photo models, who he alternately staged in a sporty carriage and modern clothing or, conversely, in front of a mill and in a dirndl. Many of the pictures appear to be snapshots, but were prepared over a long period of time. Like other colleagues, von Perckhammer made no distinction between private and public photographs and sold both to the press.

Perckhammer's photographs also refer to Ullstein's publishing history. Although he received extensive commissions from Scherl, the photographs at Ullstein – from 1937: “Deutscher Verlag” – speak of a collaboration lasting several years. Not only early works from the time of his stay in China from 1913 to 1927 can be found at ullstein bild, but also evidence of the most diverse journeys and events of later years. Large parts of his war reporting are excluded. What insights can be gained from this meeting of press publisher and photographer?

Captions prove that Perckhammer worked as a special photographer for Ullstein's competitor August Scherl. At the time, the publishing house published the entertainment and society magazine Sport im Bild (1895-1934), which was continued as Silberspiegel (1935-1944) after the Gleichschaltung. Perckhammer is represented in almost every issue from the late 1920s to the 1940s.

However, like many illustration and reportage photographers of his time, Perckhammer did not work exclusively for Scherl; he worked for several magazines and publishers. His pictures were widely distributed. Before 1933, for example, they were also printed in the Ullstein magazines Die Dame (1911-1943) and Der Querschnitt (1921-1936). This was controlled either directly by the photographers or by agencies, some of which continued to distribute images even years after they were taken. This is certainly how the China pictures, which date from the 1910s but were only published in Europe after 1927, after his return from Asia, came into the archive. What we know about Perckhammer today is that he worked internationally with the agencies Photo Globe (France), Culver Pictures (USA) and Schostal (Austria). Unfortunately, I was unable to clarify at the time whether he received direct commissions from Ullstein. Unfortunately, the written sources are often poor, publishing documents are lost, so that the photographic objects provide the best starting points for reconstructing the story. In Perckhammer's case, it was possible to verify in which magazines his pictures were published and thus with which publishers he worked. That's how I came across the Ullstein publishing house. However, we often do not know what kind of collaboration this was – i.e. how exclusive or less exclusive the working relationship was, how the remuneration and (textual) interpretation of the photographs presented were structured, whether and how much say the photographers had in the process – as the photographic objects often provide no information beyond the place and time of publication.

Perckhammer's most active period ended soon after the outbreak of war. From 1940 onwards, he published in the relevant foreign magazine Signal (1940-1945), where his pictures were then recognizably charged with National Socialist pathos: Strong light/dark contrasts are used, cloud formations are dramatically retouched and the soldiers shown are ideologically exaggerated by being seen from below. In Perckhammer's oeuvre, however, shots like these are in the minority. After 1939, his work is characterized above all by superficially documentary, formally inconspicuous photographs, which he took in occupied cities such as Danzig and Paris, but also at other focal points of the war. Particularly noteworthy here are pictures from around 1941 showing Jewish inmates in the Lublin ghetto and Soviet soldiers transporting prisoners. There is evidence that some of these photographs were used by the Nazi regime to construct an image of the enemy. His journalistic career ended after this, which leads to the conclusion that he was primarily successful as an illustration and reportage photographer, not as a war correspondent – also because the non-news business of illustrated magazines demanded images that entailed a certain openness and which he – a commuter between tradition and modernity – mastered ideally.

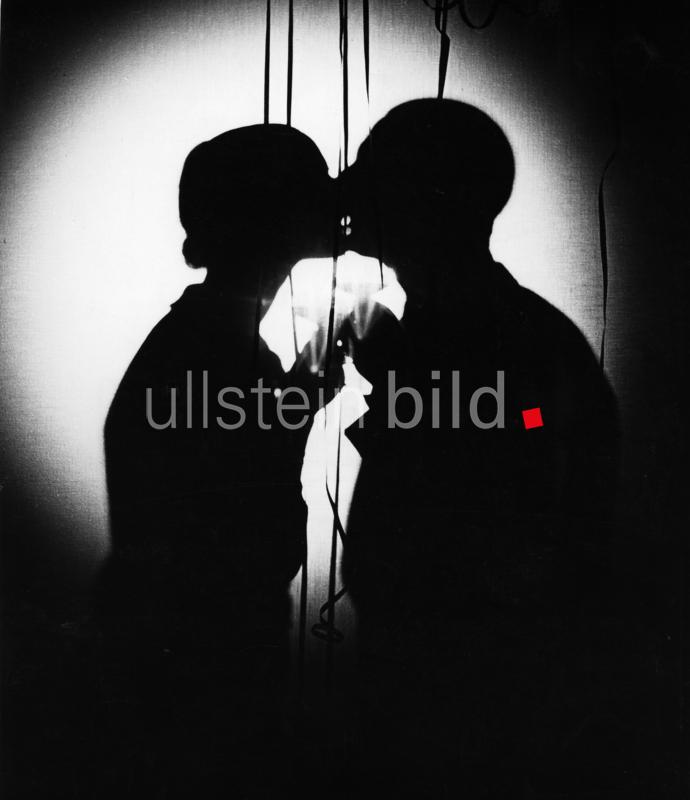

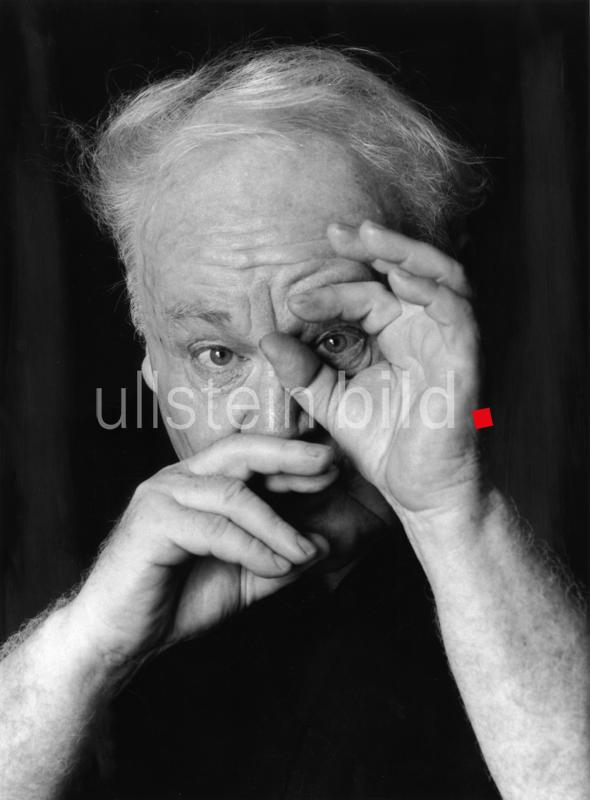

On another forward-looking topic: you are planning an exhibition in Munich to mark the 100th birthday of photographer Stefan Moses (1928-2018), whose estate is housed in the Münchner Stadtmuseum. ullstein bild in Berlin also holds a remarkable collection of works by this photographer, which date back to their collaboration during his lifetime. What will be the focus of the exhibition?

The Munich City Museum has been closed since the beginning of this year due to a long-awaited, extensive general renovation. The renovation work is scheduled to last until 2031, during which time we will have no permanent temporary exhibition space; it is therefore not yet clear whether the project can actually be shown in Munich or whether it will be shown outside the city, in another museum dedicated to photography. This also depends on the partnerships we are able to forge in the coming years.

After Moses' estate became part of our photography collection in 1995, my predecessor Ulrich Pohlmann succeeded in acquiring the rest of his photographic work after the photographer's death. In total, there are around 450,000 negatives and almost 100,000 prints of all qualities (exhibition and working prints, baryta, PE, digital prints). We are currently sorting the new partial estate in order to merge it with the Moses archive and to be able to process the entire work in the coming years. An upcoming exhibition will then have to be based on the new findings that emerge from this work, so I'm not currently too concerned with the exhibition concept. What I hope is that the newly received material from Moses' series “Emigrants”, “Masks” and “The Great Old Ones” will often allow a more diverse gender ratio to be reconstructed than was evident in the existing material. The relationship between reportage and so-called art photography will certainly play a role. And I am curious to see what unforeseen – regional and national – themes we will find. Most recently, I had a box of photographs from the Oktoberfest in my hand, which I am interested in due to a current research project on joke photographs at fairgrounds. In any case, an upcoming exhibition must go beyond the retrospective shown at the Stadtmuseum in 2002, for example by focusing more strongly on the conditions under which Moses' pictures were produced and the contexts in which they were distributed, in order to be able to look at the well-known pictures from a new perspective.

Reframing the Collection, the new research site of the Photography Collection, which went online in June 2024, deals specifically with the photographic holdings of the Münchner Stadtmuseum, developing new perspectives and new contexts. What criteria and goals are you using to develop this project?

We have conceived Reframing the Collection as a platform that uses the digital space in its own mediality. Text contributions are supported by audio commentaries and professional video recordings. The site has an anti-chronological structure, with the individual contributions linked to each other via keywords so that they can be sorted according to topics such as printed photography, landscape images, feminism and the like. It grows cumulatively. Over the years, a rhizome-like network will be created that will provide an ever-changing picture of the photography in our collection.

The procedure is as follows: several individual contributions are created for selected bundles from our collection, which present the bundle from a content perspective, but also take a methodological and collection-historical look at the holdings. In concrete terms, this means that we present collections and photographers that have received little attention to date and at the same time ask why they have been underrepresented to date. How objects become visible in archives is an overarching, systemic question that goes beyond the individual case and begins with the decision to inventory, index and digitize. In this way, we want to look at the collection from its edges and – with a self-critical eye – discover what has been overlooked.

The site is currently maintained by the scholarship holders of the Alfried Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach Foundation. It has gone online with four contributions by Clara Bolin, which deal with Lotte Eckener (1906-1995), a photographer and publisher who was mainly active on Lake Constance, but whose work has received too little attention due to its categorization as applied photography. Gender relations also played a role here. The next articles will follow in December this year and are written by Christopher Lützen. They will shed light on the photography of the Munich photographer Norbert Przybilla (1953-1996), who worked in a queer context, and question the heteronormative structures in which the works are inscribed in our collection and exhibition history.

Thank you very much, Ms. Schönegg, for this interview!

Questions: Dr. Katrin Bomhoff, ullstein bild collection.

First published on October 18, 2024.

In the gallery you can see a selection of images on our topic, the corresponding dossier can be found at ullstein bild.